WARNING: The following article contains language which some people may find offensive. VSA articles reflect the terminology used in the country featured, and in this instance has referred to ethnic groups by the titles used by the South African Government when reporting population statistics.

Article by Trevor Richards, ex-VSA Programme Manager

In his 1993 report ‘Towards Violence Free Elections in South Africa’, Mr Justice Goldstone, regarded by many as one of the most trusted members of South Africa’s white establishment, wrote ‘there is no element of the pre-election process more important than voter education. Without this, the electorate’s rights are threatened, and with that, the integrity of the democratic process.’ The logic of his assessment was inescapable, and pointed to a massive task ahead prior to South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994.

Twenty-two million citizens were eligible to vote. Seventeen million of them had never voted before, knew nothing about what voting involved. It would be a new experience, made all the more more difficult by the fact that many of them were functionally illiterate. The need for voter education was obvious.

The first four volunteers VSA sent to South Africa arrived between October 1993 and February 1994, and were involved in helping prepare the country for its first non-racial, democratic election.

East London VEETU (Voter Education and Training Unit) team, Pat, Pumia, Patina, Bandile, Carmel, Mashumi

Many assignments are exhausting and rewarding in equal measures, and for these VSA volunteers the association with pivotal events in contemporary history made it even more grueling. Two weeks before the country went to the polls, VSA’s Africa Programme Manager, Trevor Richards, arrived in South Africa to discuss with VSA’s four volunteers the progress of their work.

Driving into Johannesburg from the airport, it was obvious that there was an election taking place. Billboards and posters were everywhere. A mix of well known and established political parties, together with others I had never heard off - 19 parties in all - were proclaiming their virtues, shouting out their message as they vied for the attention of passing motorists. My favourite billboard, from the popular Johannesburg radio station Radio 702, read ‘Pick your Party carefully. The last one went on for 40 years.’ Displayed high above the freeway on the northern outskirts of downtown Johannesburg, it was a stark reminder of South Africa’s recent, bloody past.

My schedule gave me three nights in Johannesburg, before moving on to Klerksdorp, 170kms to the south west, where one of the four VSA volunteers, Pam Charteris, was based.

In Johannesburg, there were meetings with the South African Council of Churches, who had organised much of my first 1992 visit to South Africa; with former New Zealand Foreign Minister Russell Marshall, who was Chair of the Commonwealth Observer Mission to South Africa; and with the ANC. Through more than 20 years of anti-apartheid campaigning, there had been many contacts with the ANC. My Johannesburg meetings helped bring me up to speed with recent developments. There had been so much, both welcome and unwelcome, to catch up on. Political campaigning had been energetic. Many thousands of election officials and monitors were being trained. Thousands of voter education efforts were underway to prepare the electorate for 26 April, the first of the three days that had been set down for voting.

Hanging over the campaigning and these frenetic preparations was a dark shadow. In the four years leading up to the elections, 14,000 had been killed in politically motivated violence. In the month prior to my arrival, the death toll had exceeded 500. Was South Africa capable, even at this late stage, of one final, unspeakable act that halted the election in its tracks? I finished these meetings with a head full of different scenarios, all the way from the gloriously optimistic to the bleak and desolate.

Weirdly, with so much political violence in evidence, not one political poster or billboard had been defaced. These were being shown astonishing respect. In western democracies, they are commonly the first victims of any election campaign, vandalised or torn down. In South Africa, they were a protected species. Under the Electoral Code of Conduct, agreed to by all parties contesting the election, large fines were imposed on anyone caught destroying or removing campaign materials promoting those of political opponents. As a consequence, campaign posters and billboards were not only everywhere in abundance - I doubt that there was a lamppost anywhere in urban South Africa in April 1994 that was not plastered with them - but they were also in mint condition.

Saturday 16 April, was a lovely day for a rally. Weather-wise, most days were. In the afternoon a group of us went to an ANC rally at Zoo Lake, a popular public park in the leafy northern suburbs. The crowd was large and enthusiastic, predominantly black african, although a few whites could be spotted. There was a great spirit; lots of singing and dancing and happiness. Given its location, it was probably as close to a middle-class gathering as ANC rallies got.

Before leaving Johannesburg, I had been tempted by a raffle which was being enthusiastically promoted. Posters for it were prominently displayed in just about every political and NGO office I visited. After a while, I realised that the posters were not all for the same raffle. They were all different raffles. What made them look so much like each other was that they all had the same first prize: an all expenses paid trip for two to Havana, Cuba. Only in South Africa, and probably, only in 1994!

As I left Johannesburg for Klerksdorp to spend time with Pam Charteris, police were in the process of encircling Johannesburg with barbed wire. The authorities were determined to prevent the latest group of marchers from the Inkatha Freedom Party from getting anywhere near to the centre of the city.

Pam was a dental nurse, and a former National Party organiser in the South Island. In Klerksdorp, the first capital of the old Transvaal Republic, she worked for the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC). Klerksdorp is an Afrikaner town where crimplene had never really gone out of fashion, where meat is king, vegetables are treated with disdain and bookshops are regarded by most in the white population as subversive.

The IEC worked in four areas:

(1) training those who administered the elections. In less than three months, the IEC’s task was to train 10,000 of these officials; (2) training 10,000 election monitors. Their job was to observe and report on all aspects of the electoral process, including political meetings, party canvassing, advertising and the election itself; (3) adjudicating the outcome of the election. Within ten days of the election, the IEC was required to declare whether the elections had been free and fair. (4) The IEC was also involved in voter education, although the principal actors in this field are South African NGOs.

For Pam, it had been a 12-hour a day, seven days a week, job since her arrival. It was exhausting just listening to what was expected of the IEC, and what a week’s work for Pam entailed. Her specific task with the IEC was to advise on the training of 1,500 IEC election monitors. Each voting station was required to have at least one monitor. I suggested to Pam that ‘chaotic’ would seem to be the best way to describe the IEC office in Klerksdorp. Looking around, desks were piled with papers and drained coffee cups.

Phones were constantly ringing. Clusters of people were sitting, working, rushing, talking, stopping mid-sentence to deal with some other matter, laughing, shouting. ‘Chaotic?’ Pam agreed, attributing it to the magnitude of the task and the almost impossible timeframes to which the IEC was working.

Her description seemed to perfectly summarise the situation: ‘It has been like building a ship at sea’.

In the afternoon I sat in on an IEC election monitor training workshop taken by Angela, a young Afrikaans former public prosecutor. Participants were bright, sharp and enthusiastic. After the session Angela told me that her work with the IEC was ‘the most worthwhile thing I have ever done’. The opening up of the political landscape had provided an opportunity for some of those from conservative backgrounds to find their better angels.

After three nights in Klerksdorp, it was on to East London to meet with the three remaining members of the VSA team. The Eastern Cape, one of South Africa’s poorest regions, was set to become the principal focus of VSA’s programme in South Africa.

Trevor Richards, Rex Bloomfield, Patina Edwards and Pat Webster

VSA’s team in East London, all involved in voter education, comprised Rex Bloomfield, Pat Webster and Patina Edwards. They all worked for the Voter Education and Elections Training Unit (VEETU), which was a part of Afesis Corplan, a community grassroots organisation and VSA’s local project partner. Established in 1984, it worked alongside the marginalised, disenfranchised poor. The principal role of the VSA team was to make people aware of the new political system, explaining why voting was important, how one votes and where and when the vote will take place. The area they covered was large and travel extensive. Lady Grey, where one voter education session was held, is over 300kms from East London.

Rex was an old hand at voter education. Before South Africa, he had spent a year with VSA in Cambodia, working with the UN voter education programme. In the Eastern Cape, in conjunction with local teachers, he initiated an ‘Education about Democracy’ project aimed at helping schools teach about issues of democracy and human rights. Over half of the 250 schools in the region became involved in the project.

In New Zealand Pat Webster worked for the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions, and was a senior Vice President of the New Zealand Labour Party. She was responsible for developing VEETU’s workplace voter education programme. This involved closely working with trade unions. In the month before Christmas, she was running two workshops a day at the local Nestle factory, training more than 2,000 workers. At the local hospital she trained over 1,500 workers.

Brickworkers in Williamstown in mock voting session during the Voting Education Workshop

Patina Edwards, a policy analyst with Te Puni Kokiri, shared her time between Pat and Rex. I accompanied Patina to a voter education workshop in King Williamstown, 60 kms from East London. Steve Biko was born here. The session was for 50+ building labourers.

She asked us all to introduce ourselves. I gave my name, adding “I work for the organisation which recruited Patina to come to South Africa and work on voter education”.

A chorus of ‘thank you’ ran around the group. Later that day I write in my Field Trip diary ‘Every day, something happens which makes my day. That was today’s moment.’ These sessions are not short, and typically last for two hours. In King Williamstown the session was conducted outdoors in the blazing heat. At no stage did attention show any sign of waning.

After introductions, the session began with a discussion on why people should vote. There were no shortage of excellent reasons put forward. Most of these revolved around the need for a much fairer deal - more jobs, better education and health care, more houses.

The answers given were worrying, indicating an unrealistic level of expectation as to what would happen in the event of an ANC victory. I still recall a heart wrenching letter written to the Cape Times in the period immediately following Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. ‘Mr Nelson Mandela has been out of jail now for five days’ the letter read. ‘Why are we, the people of the Cape Flats, still waiting for houses?’

The discussion on how to vote was the longest part of the two hour session. For light relief, students dressed up as clowns acted out common misconceptions which people had about the voting process. In the course of this segment, when and where to vote was discussed. After this, everyone participated in a mock ballot. By the time of the elections, information about voting had reached 98% of black South Africans. VSA volunteers had taken more than an estimated 100,000 through the voting process.

"the logistics of the exercise now seemed to be comparable, not to building a ship at sea, but to constructing a submarine underwater."

As the first day of the election approached, there was a tremendous energy, excitement and enthusiasm on the streets. It was palpable. So different from my two previous visits in 1992 and 1993. It was a bit like New Zealand on Christmas Eve - only people were not waiting for Santa Claus; they were waiting, expectantly (in the most part), for their ANC government. One of the women cleaners in the hotel told me excitedly ‘I’m voting for the ANC’. She said it with such a high degree of commitment and enthusiasm. The following day, walking back to my hotel after dinner, a young black african guy passes me on the street. We said hello to each other and then he smiles, looks at me and shouts ‘Viva ANC’.

This enthusiasm had been evident at ANC rallies for months. Pat Webster had vivid memories of the day she heard Mandela speak at a huge ANC rally in Bisho in the Ciskei bantustan. ‘It was a wonderful day, and when Mandela arrived, it was magic. I shan’t forget it. The bit I loved the best was when he was telling the crowd how to fill out their voting paper. “You will see the name of the African National Congress” (cheers from the crowd); “you will see the ANC symbol” (bigger cheers from the crowd); “then you will see a picture of a young man you will recognise” (stunned silence and confusion); “he will be a young man with white hair” (delirious cheers of approval). Oh how good he was.’

But will South Africa be ready in time? Three days out from the election it was estimated that between 1M-1.5M in the Eastern Cape alone were without documents. Violence remained a threat. Even at this late stage, could it sabotage the election? Two days out from Election Day, as I am writing pieces for the New Zealand print media, reports came in of a car-bomb blast in downtown Johannesburg, close to ANC Headquarters. Nine had been killed. No one claimed responsibility, but bombs had been the favoured weapon of white extremist groups opposed to the end of white rule. Worse was to follow. The day before the election a 220-pound bomb ripped through a crowded black african taxi stand in Germiston, killing ten. Later, two died in a restaurant blast in Pretoria. Eleven polling booths were bombed. Over two days, 21 were killed and almost 200 injured, but outside of the East Rand and the Natal Midlands, peace largely prevailed. East London was buzzing

politically and pretty much free of violence.

Tuesday 26 April, Day One of the election was a lovely 27C in East London. There was a big South African Police/South African Defence Force presence in town - scarcely surprising given the events of the past 48 hours. In the morning I took photos of impossibly long queues outside polling booths. There were also very long queues of people (all black african) outside the Home Affairs office, applying for their ID cards so as they could vote.

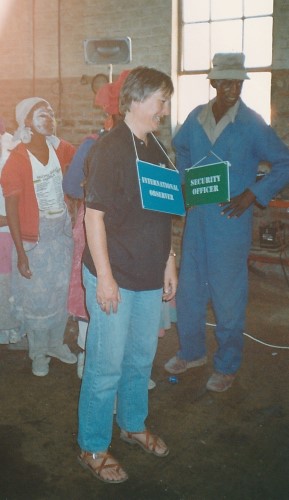

Pat Webster, Voter Education Workshop

I met up with Pat Webster in the early evening. She had spent time with Steve Tshwete (Number 12 on the ANC’s National Assembly list). Pat reported that Steve was concerned things had not been going smoothly - and the first day, for special voting, was supposedly the easy day. It had been, as The Star’, Johannesburg’s main English speaking newspaper said the next day ‘Joy, tarnished with hitches. Euphoria and frustration characterised the day of special voting - and violence took a back seat.’

With special voting out of the way, day two was always seen as being the big voting day. It was to be a day of many problems. There were huge shortages of the ink being used to mark the hands of those who had voted. Polling booths ran out of voting papers, others ran out of ballot boxes. Many polling booths were very late opening. Some queues of people waiting to vote exceeded 6,000. At 4.30pm the ANC called for the following day to be declared a public holiday so as to facilitate voting. Somewhere in the midst of all of this, there was a bombing at Johannesburg’s Airport, injuring ten. Late in the afternoon the IEC announced that (1) in order to meet the shortfall in ballot papers, an extra 9.3 million were to be printed and distributed overnight, and that (2) in order to facilitate voting, the following day had been declared a public holiday.

It was difficult to keep up with developments. Would the emergency ballot paper exercise really be successful? To extend Pam’s analogy, the logistics of the exercise now seemed to be comparable, not to building a ship at sea, but to constructing a submarine underwater. Somehow, South Africa got through the day. At one minute past midnight, to the strains of the Republic’s new national anthem, we watched the new South African Flag being raised. Our celebrations that night were enthusiastic.

Thursday 28 April was a much quieter day. De Klerk announced in the evening that following a request from the IEC, he had approved the extension of voting into a fourth day in Northern Transvaal, the Eastern Cape and Natal. He didn’t really have a choice. Without this extension, it would have been difficult for the IEC to declare the elections free and fair. Failure to do this would have created a worst case political nightmare.

After four days of voting, my head was packed full with vivid memories. The front page of the 27 April edition of the Johannesburg morning newspaper The Star kept flashing in my mind. Above a photo of four old women - two black african, two whites - in a queue waiting to vote, the banner headline read ‘Vote, the beloved country’. It had been a very long journey from Cry, the Beloved Country. Alan Paton, wherever he was (he died in 1988), would have been smiling.